What is the immutable core of roleplaying games? Let’s consider this basic game loop described in D&D 5e:

[T]he game follows a natural rhythm […]:

The DM describes the environment.

The players describe what they want to do.

The DM narrates the results of their actions.

Seems pretty non-controversial, right? But consider these two quotes from Swords of the Serpentine for contrast:

You[, the player,] have a responsibility alongside the GM to help create the world, so don’t be surprised when you ask a question and they answer, “You tell me.”You will often get to customize the world unless your GM already has something in mind, so expect to have an input into details of the setting; and to describe where you are and what’s nearby when trouble occurs!

(page 4)

It’s good to remember that players describe their General ability use in whatever way is coolest or most fun […].

(page 41)

Alright, so it’s not a given that describing the environment or narrating the results of PC actions is in the sole purview of the DM/GM. In fact, some RPGs do away with the GM role entirely or make it optional.

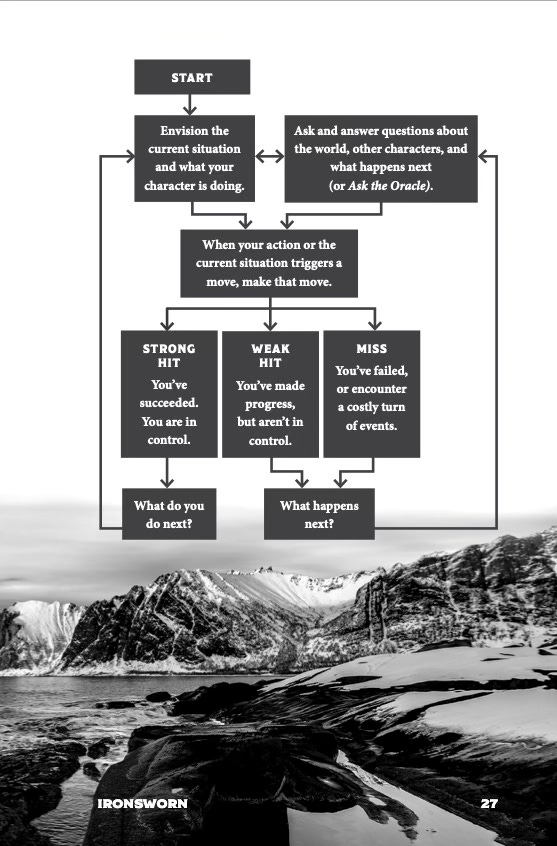

A famous example is Ironsworn (a game designed to play on your own or as a group – with or without a GM) which explains the core game loop with the following flowchart:

Unlike the summary from D&D, it puts the mechanics front and center. I’d recap it as follows:

Envision the situation.

If necessary, clarify by way of conversation or consulting random tables.

When an action triggers the rules, follow the rules.

Consider how the situation has changed and go back to point 1.

Ironsworn, like so many games, has been influenced by Apocalypse World, which describes the core game loop on page 9:

You probably know this already: roleplaying is a conversation. You and the other players go back and forth, talking about these fictional characters in their fictional circumstances doing whatever it is that they do. Like any conversation, you take turns, but it’s not like taking turns, right? Sometimes you talk over each other, interrupt, build on each others’ ideas, monopolize and hold forth. All fine. These rules mediate the conversation. They kick in when someone says some particular things, and they impose constraints on what everyone should say after. Makes sense, right?

[…]

The particular things that make these rules kick in are called moves.

It is perhaps my favorite description of what an RPG is. Vincent Baker can somehow make complex concepts sound obvious and fun.

Alright, we’re getting onto something. Let’s see what we’ve learned.

Firstly, the game seems to always be about one or more fictional characters. I can’t think of a single RPG where that is not the case. Since RPGs can be played with or without a GM, and with one or more people, and since the GM role isn’t the same across RPGs, let’s define the universal core gameplay loop as follows:

Envision and present (usually describe) the situation your character(s) are in.

Continue until a game rule is triggered, in which case resolve the rule.

Consider how the rule’s resolution has changed the situation and incorporate it into the fiction.

Individual players’ roles in this process can differ, and additional tools can be used depending on the game.

The Immutable Core of Roleplaying Games

Based on the above, the elements necessary to call an activity a roleplaying game seem to be as follows:

one or more human player(s),

active imagination employed to describe a fictional situation,

one or more character(s) who the imagined events revolve around,

rules interacting with the fiction: they are triggered by the fiction and put constraints on the fiction that follows.

In other words:

A Roleplaying Game is a human activity structured around imagining and depicting fictional events involving one or more characters and mediated by certain rules.

The Wikipedia definition talks about “assuming the role of characters in a fictional setting”. I like that my definition doesn’t. Firstly, it reflects better the “third person perspective” a lot of players are more comfortable with. Secondly, it fits better with the roots of the hobby (and – by extension – with much of the OSR) where the player characters served more as avatars for the players to interact with the fictional world (and a player would often control multiple characters such as henchmen and retainers).

I’ve purposefully used the word “depict” instead of “describe” because we don’t only talk. We gesticulate, we cosplay, we draw, we ask ChatGPT to draw. We use various media to express what we’ve imagined.

Go To (Design) Jail!

Now, let’s try and answer the question from the title. Is Monopoly an RPG? It is certainly a human activity. It is certainly mediated by rules. It arguably has characters, as abstract as they are, and it presents a fictional scenario. However, it is not structured around imagination. We can certainly imagine real hotels being built on Pennsylvania Avenue but it is not necessary for a game to happen. You can play it strictly procedurally, and it still works.

The line between RPGs and boardgames is admittedly fluid. In particular, I find John Harper’s design sensibilities push the envelope and encroach on traditional boardgame territory. He tends to incorporate strong procedures which still work even if you limit the imaginative component. Some examples include the downtime procedures in Blades in the Dark and Agon. But the difference is immediately palpable. When we played Blades and speedran downtime, we very quickly started commenting that it didn’t feel like an RPG anymore. It proves that the boundary is there, and it can be grasped intuitively. I think the question: What is the gameplay structured around? helps define it.

Another corner case are gamebooks, and I still feel our definition helps draw a boundary here. A gamebook is structured around pre-set branching decision points: it certainly invites imagination but it is not what drives the gameplay. So, perhaps RPGs are not so much “fiction first” as they are imagination first?

So… Now What?

I have no real end game here beyond a philosophical satisfaction of a definition I am happy with. That said, meditating over the definition made me realize a few things.

One: RPGs are a profoundly human activity. You know I am not too happy with the way AIs encroach on the hobby, and this definition makes it even clearer why. RPGs grow from very human roots: from our imagination, from our conversations, from our self-expression. Having a functional, healthy imagination is good for you, and roleplaying games help you practice it. They give you a way to interact with challenging realities in a safe environment. They help you look at things from surprising perspectives. They are educational and therapeutic. At the same time, they also engage and exercise your mind.

Two: specific roles: player, GM, and anything in between, seem to be optional. I like the modern trend of gamifying and restraining the GM role (like in Grimwild, Daggerheart or in Modiphius’ 2D20 system, among others). You also have Riyuutama where the GM has their own character: an actual dragon. You have games with no GM at all. You have games encouraging player input into parts of the setting. But all in all, we have been pretty conservative with player role definitions. I think there is ample room for innovation in this area. I would like to see games embracing asymmetry in player roles, giving them control over different parts of the story, divided by other criteria than the character one controls.

Three: perhaps the discussions around fiction first vs. mechanics first are moot, and we should see the fiction and the rules as two intertwined parts of the game, inseparable like yin and yang. In games such as Microscope, you start with a mechanical framework that guides the whole process. It is arguably rules-first. But it is no less an RPG than D&D (and dare I say, rules go more out of the way in Microscope than they do in D&D).

Four: speaking of Microscope, while characters seem to be a necessary lens through which we tell stories (by virtue of being humans), characters can be permanent or transient. I think this is another area of possible innovation in RPGs. What even makes a character? In Life Among the Ruins, families are treated as playable characters, for example.

Five: I’d considered using the expression “fictional story” in the definition but I opted for “fictional events”. I think it is an important distinction, as many play styles focus on an emergent narrative and deemphasize the need for a cohesive story.

I enjoyed this reflection on what a roleplaying game is. I realize my definition will become one more on a long list of definitions, and won’t find its way to encyclopedias everywhere any time soon. But it helped me understand and appreciate my hobby a little bit better, and I hope it did the same for you.

I don't think I've heard of ironsworn before, But that resolution chain is why I love powered by the apocalypse so much for teaching table top to people new to the genre. I found most people don't have a hard time understanding the theater aspect of RPGs that is an overlooked component of what makes certain games special I feel. Where do you think ARGs rest in the larger sphere of collaborative gaming?

At this point I came to a conclusion that definitions consisting of conditions that are true for all RPGs are somewhat of a dead end

My current understanding is that there's a set of traits associated with RPGs, and the more of them a given game has, the "more of an RPG" it is, with some games indeed being in a weird limbo between RPGs and other games or forms of entertainment